好久不见 (hǎojiǔ bùjiàn) = Long time no see.

好久不见 (hǎojiǔ bùjiàn) = Long time no see.

I cannot say that my recent lack of posts has given me much respite because I have been preoccupied with work. In addition to my college work, I have been doing a lot of research into various factors of China, which has included efforts to learn more about the Chinese economy and reading Chinese literature. I have been quite keen to share some of my findings, but did not want to provide incomplete facts (…which idiom does that remind you of?). I felt the urge to create today’s post because of something that has taken my focus as of late. This is something that I came across on several occasions during my Mandarin lesson earlier today and had lead to the title of todays post.

If you are familiar with the Chinese language or have been following my posts then you will recognize the contrast in the Chinese language to conventional methods of communication such as the English language. Something that makes me appreciate the complexity of Chinese is the similarity that certain characters share. I remember scenes of being in my Chinese lesson and staring at a character on the white board with certainty of its pinyin, only to find that it is just a character very similar to the one I had been thinking about. At times like that I could not fathom how the composition of the character could so heavily impact its meaning.

Something I often get asked is if I ‘find Chinese hard’. My response is usually that Chinese is one of the hardest languages to master, however I find it enjoyable and thus have managed to cope with its complexity. However recently when I have been asked by my peers to talk about the Chinese language I tell them that although you may never be fluent in any language, it is certainly impossible to be completely fluent in Chinese. This is not a result of pessimism (the glass is always half full as they say), but because even native citizens of China come across characters that they are unfamiliar with. Even so we should not accept defeat in our mastery of Chinese on the basis that Chinese citizens occasionally stumble (the reason is sometimes lack of schooling); but we should be aware of the fact that some characters have a certain pinyin (transliteration) in one sentence, and then the same written character can have an entirely different pinyin in another sentence. If you had only learnt one pinyin reading for a certain character then it is likely that you will make an error when reading the character as you encounter it in a text because you will read it with the particular pinyin that you had learnt, when in fact it is meant to be read with a completely different pinyin. I hope I have not lost you with my explanation, the similarity in characters is a strange occurrence in the Chinese language but it cannot go unnoticed.

Sometimes it is not that a particular character will have a different pinyin reading depending on the sentence; it is in fact more common to find two (or more) characters that may look identical on the first glance, but closer inspection will indicate that there are differences in their radical components. In a nutshell what I have just explained illustrated the title of this post. I suppose I should demonstrate this with ‘an example or two’…So let’s play a round of ‘spot the difference’. I will indicate each example with a number as a prefix, the first character, then a forward slash, followed by the next character, and then a comma before the next example. 准备好吗/Ready?

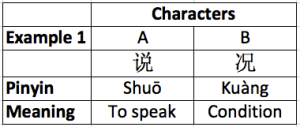

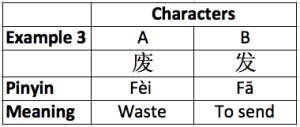

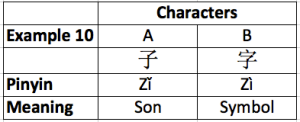

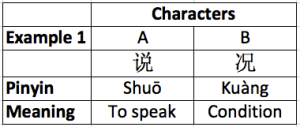

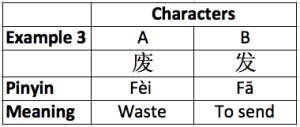

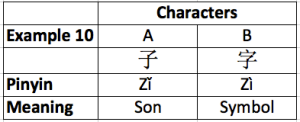

1说/况, 2处/外, 3废/发, 4去/法/却, 5或/成, 6水/永, 7人/入, 8如/加, 9白/自, 10子/字, 11员/贵, 12不/下, 13大/天, 14免/晚. How did you do?

When you learn your first Chinese characters it can be daunting to be shown such similarities, so to see them openly in a list is quite hard hitting. Today I had experienced denial in my Chinese lesson when I noticed example number 1. Often in lessons or when I am reading, I notice these similarities and they can cause me to pause so that I can confirm a radical. For example, although the difference is not as implicit as the others, today I got confused with example number 5 when being asked to translate a text.

The post would be a bit unfinished for me to provide these examples without explaining how they can be differentiated. Therefore I have created a few tables (like the ones from my post ‘Chinese basics kept basic’) in order to define the characters and show you how they are in fact different although they may look the same.

I do not view this aspect of the Chinese language in a negative manner (after all I did make it into a game), rather I think that it’s interesting and motivates me to focus when translating Chinese texts. If you are familiar with Chinese language then I invite you to provide some of your observations 🙂

I do not view this aspect of the Chinese language in a negative manner (after all I did make it into a game), rather I think that it’s interesting and motivates me to focus when translating Chinese texts. If you are familiar with Chinese language then I invite you to provide some of your observations 🙂

If you come across characters that seem identical but actually have a minor difference in their radical components, good luck 世界.

从欣妍 – From Xinyan.

EDIT: Take a look at the character 长. It is an example of a character that can have a different Pinyin and meaning depending on the context of the sentence. 长 can be read as either ‘chang’ or ‘zhang’. I wanted to give some sort of example when I had originally written the post but my mind had gone blank then, perhaps you should wish me good luck! [That also reminds me, the character for wish (zhù) is 祝, and if you compare it with the picture at the start of the post you may find further similarities…].